Why Are Some Trees Painted White?

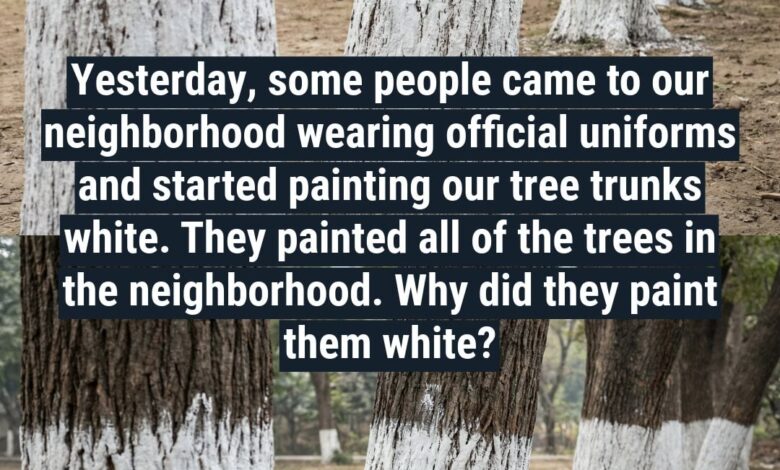

Those white-painted tree trunks you sometimes notice in orchards, parks, and along rural roads aren’t there for decoration, tradition, or whimsy. They’re the result of a quiet, practical decision rooted in plant physiology and hard-earned experience. Painting trees white is a simple but effective way to protect them from a specific kind of damage that happens when winter sunlight and freezing temperatures work together in the worst possible way.

During cold months, especially in late winter and early spring, the sun can be deceptively strong. When it strikes the dark bark of a tree, particularly on the south or southwest side, it can warm that surface significantly—even when the air temperature is well below freezing. The tree’s tissues respond to that warmth by expanding slightly, as living cells always do when temperatures rise. But when night falls and temperatures plunge again, that same area cools rapidly and contracts. This repeated cycle of warming and freezing creates stress inside the bark.

Over time, that stress can cause the bark to crack or split open. This injury is known as sunscald, and despite the name, it has nothing to do with burning. It’s a mechanical failure caused by extreme temperature swings. Once the bark splits, the tree’s natural defenses are compromised. Open wounds allow moisture to seep in, fungi to take hold, and insects to invade. What starts as a temperature problem can quickly turn into disease, rot, or structural weakness that affects the tree for the rest of its life.

Young trees are especially vulnerable. Their bark is thinner and less insulated than that of mature trees, making them far more sensitive to temperature changes. Fruit trees—such as apple, peach, cherry, and citrus—are common candidates for white-painted trunks because growers have long known how devastating sunscald can be to productivity and longevity. A single bad winter can permanently damage a tree that took years to establish.

White paint helps solve this problem in a straightforward way. Light colors reflect sunlight rather than absorbing it. When a tree trunk is coated with white paint, it stays cooler during the day, reducing the temperature difference between day and night. With less dramatic expansion and contraction, the bark remains intact. The tree still experiences winter, but without the internal shock that causes splitting.

The paint used is not just any paint. Arborists and gardeners typically use water-based latex paint diluted with water, often at a ratio of one part paint to one part water. This creates a thin, breathable coating that reflects light without sealing the bark. Oil-based paints are avoided because they can trap moisture and interfere with the tree’s natural gas exchange. The goal is protection, not suffocation.

Application is usually done once a year, typically in late fall or early winter before the strongest freeze-thaw cycles begin. The paint is brushed or sprayed onto the lower portion of the trunk, starting at the base and extending up to the first major branches. This area is the most exposed and most likely to suffer damage. In orchards, rows of white-painted trunks may look strikingly uniform, but each one represents a preventative measure taken long before any injury appeared.

While sunscald is the primary reason for painting trees white, it isn’t the only benefit. The reflective coating can also discourage certain insects from laying eggs in the bark. Some pests are attracted to warmth or dark surfaces, and the cooler, lighter trunk becomes less appealing. In addition, the paint can make it easier to spot problems such as cracks, infestations, or fungal growth before they become severe.

There’s also a historical element to the practice. Long before modern plant science explained the mechanics behind sunscald, farmers noticed patterns. Trees with lighter bark survived winters better. Trees on shaded slopes fared better than those exposed to open sun. Over time, painting trunks white became a practical tradition passed down through generations, later validated by scientific understanding.

In urban environments, white-painted trees sometimes raise questions or even criticism from passersby who assume it’s cosmetic or unnecessary. In reality, it’s often a sign of attentive care, especially in climates with sharp winter temperature swings. Cities and parks departments use the technique to protect newly planted trees that haven’t yet developed thick bark or deep root systems. Without this intervention, many young trees would fail before reaching maturity.

It’s important to note that painting trees white is not a cure-all. It won’t protect against drought, poor soil, mechanical damage, or severe storms. It won’t fix existing disease or reverse rot. What it does is prevent a specific, avoidable injury—one that occurs silently, without dramatic warning, and often goes unnoticed until the damage is already done.

There’s something quietly thoughtful about the practice. Trees can’t move out of harm’s way or adapt quickly to sudden environmental extremes. A thin coat of paint becomes a stand-in for what nature hasn’t yet provided: insulation, stability, and time. It’s a small human action that doesn’t dominate the landscape or alter the tree’s growth, but simply helps it endure a difficult season.

When spring arrives and the risk of sunscald fades, the painted trunks remain as subtle reminders of winter’s strain. New leaves emerge, sap flows freely, and the tree continues its cycle largely unaffected by the danger it narrowly avoided. Most people will never notice the protection at work, and that’s the point. Preventative care is meant to be invisible when it succeeds.

So the next time you see trees standing quietly with white bands around their trunks, you’re not looking at decoration or tradition for tradition’s sake. You’re seeing a response to physics, climate, and biology—a simple, effective shield against a threat most people never think about. It’s an example of how understanding nature doesn’t always lead to complex solutions. Sometimes it leads to a brush, a bucket, and a thin layer of white that helps a living thing survive another winter and greet the spring intact.