I Took an Unplanned Day Off to Secretly Follow My Son to Catch Him in a Lie – What I Found Made My Knees Go Weak!

For years, I believed I had won the “kid lottery” with Frank. He was the kind of son other parents spoke about with a touch of envy—the boy who used a coaster without being asked, cleared the table without a heavy sigh, and treated his homework with the solemnity of a sacred text. His report cards were a rhythmic series of A’s, always accompanied by the same teacher comments: A pleasure to have in class. A natural leader.

Then, our world fractured. My husband’s illness was aggressive, a thief that stole the air from our house and replaced it with the sterile, rhythmic beeping of hospital monitors. Throughout that harrowing year, Frank remained a pillar of terrifying stability. While I sat by the hospital bed, paralyzed by the sight of my husband’s thinning frame, Frank would be in the corner with a workbook.

“Did you finish your schoolwork, kiddo?” his father would rasp, his voice a mere shadow of the booming baritone it once was. Frank would look up, offer a small, certain nod, and say, “All of it, Dad.” My husband would smile, finding a brief moment of peace in the belief that our son was untouchable, even by this.

Everything changed after the funeral, yet somehow, Frank remained the same. Or at least, that was the delusion I clung to. He became a machine of self-control. He belief seemed to be that if he never missed a day of school, kept his room spotless, and maintained his grades, our shattered life would somehow fuse back together.

I really thought he was doing okay until a Tuesday afternoon in November. I had called the school to finalize some administrative paperwork, expecting a five-minute conversation. Instead, when I mentioned Frank’s name, his homeroom teacher, Mrs. Gable, went silent.

“I’m not sure how to tell you this, Mrs. Farley,” she said softly, “but Frank hasn’t been in class for nearly three weeks. His grades began slipping significantly before he stopped showing up entirely. He isn’t in school today, either.”

I laughed, a sharp, instinctive sound of disbelief. “There must be a mistake. Frank leaves every morning at 7:30. He tells me about his math quizzes every night.”

But there was no mistake.

That evening, I didn’t confront him. I wanted to see if the boy I knew was still in there, or if he had been replaced by a stranger. When he walked through the door at 3:30 PM, his backpack cinched tight and his expression neutral, I asked, “How was school, Frank?”

He looked me right in the eye. He didn’t blink. “School was fine, Mom. We had a history lecture on the Industrial Revolution. It was actually pretty interesting.”

My hands started shaking beneath the kitchen counter. It wasn’t just the skipping; it was the professionalism of the lie. It was cold. It was practiced. I realized then that I didn’t know my son at all.

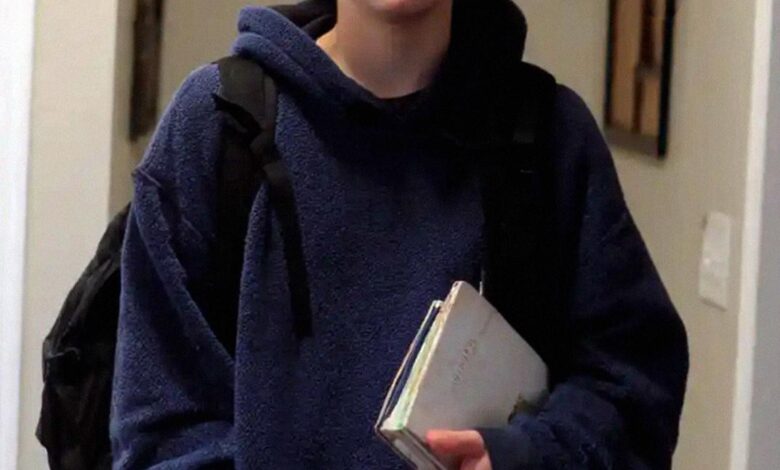

The next morning, I called in sick to work. I watched from behind the living room curtains as he rode his bike down the driveway at his usual time. I gave him a two-minute head start, grabbed my keys, and followed him at a distance. He reached the intersection where he should have turned left toward the high school. He paused for a long moment, then raced across, pedaling hard in the opposite direction.

He wove through side streets and back alleys for twenty minutes until he turned into the gates of the Oak Grove Cemetery. I parked my car under a sprawling oak near the entrance, my heart hammering against my ribs. I followed him on foot, keeping a distance, watching as he navigated the labyrinth of headstones with the familiarity of a resident.

He stopped at Row 12, beneath the massive old maple tree that was currently shedding its orange leaves like drops of fire. Frank didn’t just stand there. He dropped his bike and kneeled beside his father’s grave. When he started talking, I realized he wasn’t there for a visit; he was there to confess.

“Hey, Dad,” he whispered. His voice was so small, stripped of the “solid” veneer he wore at home. “I tried to go today. I got all the way to the gate. But I couldn’t do it. It’s too loud there.”

He picked at a weed in the grass, his fingers trembling. “Everyone is laughing. They’re talking about movies and who’s dating who. They act like the world didn’t end. And I just… I can’t breathe, Dad. I want to be sick all the time. I can be okay at home because I can keep things clean. I can tell Mom I’m fine and she believes me. But at school, I feel like I’m holding this giant weight inside me, and if I try to answer a question, it’ll slip. I don’t want to be the kid who breaks in the middle of math.”

He let out a shaky breath that hung in the cold air. “I’m trying to be the man of the house, like you said. I’m trying to take care of stuff so Mom doesn’t have to worry. If I keep everything together, she won’t have to cry anymore. But I’m just so tired.”

Standing behind a nearby monument, I felt a physical pain in my chest. I had been so proud of his “strength,” never realizing that his strength was actually a prison he had built to protect me. According to the U.S. Census Bureau and various grief counseling studies, approximately 1 in 14 children will experience the death of a parent or sibling before age 18. Among those children, many experience “parentification,” where they take on adult emotional burdens to shield a surviving parent—a weight no child is equipped to carry.

I stepped out from behind the tree. “Frank.”

He jumped, nearly losing his balance, his face turning ghostly pale. “Mom? What are you doing here?”

“I could ask you the same thing,” I said, walking toward him.

He tried to scramble back into his mask. “I was just stopping by before school… I’m going now…”

“You haven’t been in three weeks, Frank. I know.”

The mask finally shattered. His shoulders dropped, and he looked smaller than I had seen him in years. “I can’t mess up,” he blurted out. “You already lost Dad. If I start failing, you’ll have more to deal with. You need me to be solid.”

“No,” I said, reaching for his hands. They were ice cold. “I need you to be fourteen. I am the parent, Frank. It is my job to handle the bills, the house, and the grief. It is even my job to fall apart and put myself back together. It is not your job to protect me from the truth.”

“I heard you crying,” he admitted, a tear finally escaping and racing down his cheek. “Late at night. I thought if I was perfect, you wouldn’t have to cry anymore.”

The guilt was a crushing weight, but I pushed it aside for him. “You could have cried with me. We are a family, Frank. Keeping a family together doesn’t mean holding everything in a death grip. It means being honest enough to say, ‘I’m hurting.'”

His composure gave way entirely. He leaned his head against my shoulder and let out a sob that sounded like it had been trapped in his lungs for a lifetime. We stood there under that maple tree for a long time, right beside the stone that marked our greatest loss, and for the first time since the funeral, the air felt clear.

We had a long road ahead—meetings with the principal, grief counseling, and a lot of missed assignments to make up. But as we walked out of the cemetery gates together, I realized that while I had been trying to survive, my son had been trying to save me. Sometimes, the strongest thing a parent can do is give their child permission to be weak.