The Forgotten Object That Once Shaped Everyday Life And Why It Still Captivates Us Today!

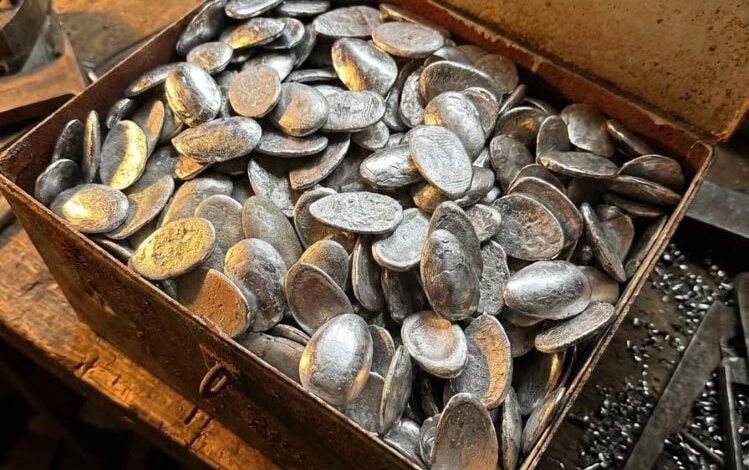

It begins as a tactile riddle resting in your palm: a weathered curve that fits the pads of your fingers with ghostly precision, a weight that balances against your wrist as if it were an extension of your own anatomy, and a curious notch that seems to wait for a specific, rhythmic task you no longer recognize. You turn it over, feeling the grain of the wood or the cold, forged density of the iron, and slowly, the realization dawns. This “mystery object” was once the steady pulse of a person’s ordinary existence. It was never intended to be an exhibit behind glass or a conversation piece on a mantle; it was shaped to serve, born from the intimate dialogue between a hand and a necessity.

In the quiet moment of recognition, the vast distance between centuries doesn’t just narrow—it collapses entirely. You are no longer merely observing a relic of history; you are touching the physical manifestation of someone’s problem-solving. You are feeling their patience, their ingenuity, and their stubborn, beautiful refusal to waste effort. These objects are the silent witnesses to a time when the world moved at the speed of a heartbeat rather than a fiber-optic cable.

The Symbiosis of Hand and Tool

The fascination we feel for these forgotten objects is rooted in a concept known as “radical embodiment.” Neurologists have discovered that when a human uses a tool repeatedly, the brain’s somatosensory map actually expands to include that object as a literal part of the body. To the artisan of the 18th or 19th century, a well-worn plane or a specialized cobbler’s hammer wasn’t just “equipment.” It was a phantom limb.

When you pick up an antique tool today, you are stepping into that ancient symbiosis. You can see where a thumb has worn a shallow groove into a handle over forty years of labor. You can feel the balance point that allowed a worker to continue their task from dawn until dusk without the crushing fatigue we might expect. These tools were tuned to the human form. In an era before mass production and interchangeable parts, a tool was often forged or carved for the specific person who would use it. It was a marriage of ergonomics and identity, creating a bond so deep that the tool and the hand eventually came to understand each other perfectly.

The Philosophy of Durability

In our contemporary landscape, we are surrounded by the “culture of the upgrade.” We live in a world of planned obsolescence, where devices are designed to fail or become aesthetically irrelevant within a handful of years. We treat our objects as temporary occupants of our lives, fleeting guests that we expect to discard.

Forgotten tools whisper a radically different philosophy of progress. They represent a world built on the values of:

- Longevity: The expectation that a single purchase or creation would last a lifetime, or perhaps three.

- Stewardship: The belief that an object is worth repairing, sharpening, and oiling.

- Intimacy: The slow accumulation of “patina”—the physical record of use that makes an object more beautiful as it ages, rather than less.

When we hold an object that has survived a century of work, we are confronted by a standard of quality that seems almost alien today. These items were made with the understanding that resources were precious and labor was an expression of one’s character. To make a tool that broke was a mark of shame; to make one that lasted was a legacy.

The Mystery of Lost Utility

Part of the captivation lies in the “mystery” itself. As technology has specialized and moved into the digital realm, we have lost the visual vocabulary of manual labor. We look at a “hair receiver” from a Victorian vanity or a “tooth key” from a colonial doctor’s kit and see only abstract shapes.

This gap in our knowledge forces us to engage our imaginations. We have to ask: What was the problem this was trying to solve? In searching for the answer, we rediscover the textures of the past. We learn about the ritual of saving fallen hair to create pincushions, or the communal effort required to turn a butter churn. We realize that our ancestors’ lives were filled with a thousand small, tactile rituals that have been erased by the push of a button or the swipe of a screen.

The Unsettling Question

Ultimately, these forgotten objects do more than just tell us about the past; they hold a mirror to our present. They ask a simple, unsettling question: When did we stop expecting our tools to know us this well?

Today, our tools are powerful but indifferent. A smartphone provides the same glass-and-metal experience to a billion people; it does not change its shape to fit your grip, nor does it develop a patina that tells the story of your specific life. It is a universal tool that belongs to no one. In contrast, the forgotten objects of the past belonged deeply and specifically to their owners. They were “psychologically durable,” forming a lasting connection that fostered a sense of stability and continuity.

By collecting, restoring, or simply marvelling at these artifacts, we are attempting to reclaim that lost intimacy. We are reaching back through time to touch a version of ourselves that was more connected to the physical world. We find beauty in the chips, the cracks, and the repairs because they chart a life well-lived. They remind us that true progress isn’t just about how fast we can go, but about how deeply we can engage with the work of being human.