The last thing Eric Claptons 4-year-old son said was See you later, Daddy

By then, Clapton had already lived more lives than most men could endure. He’d clawed his way through heroin addiction, nearly destroyed himself with alcohol, and outlived some of his closest friends—Jimi Hendrix, Duane Allman, Stevie Ray Vaughan—each a legend swallowed by their own brilliance and demons. But somehow, Clapton had survived. In 1987, he got sober. A year earlier, he’d been given something worth living for: his son, Conor.

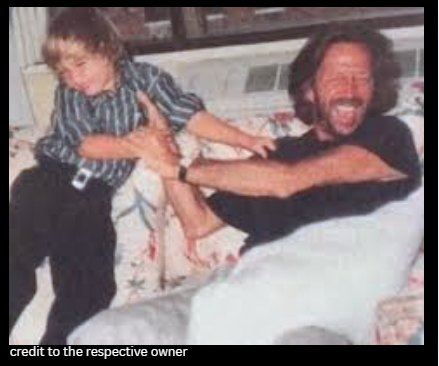

Conor was born in 1986 to Italian actress Lori Del Santo. Though Clapton and Del Santo weren’t together, they shared a bond through their little boy that went deeper than anything fame or chaos could touch. Clapton, the man who had burned through years of addiction and regret, suddenly had a reason to stay sober. Conor became his redemption.

That morning in March was supposed to be ordinary—joyful, even. Clapton was picking up his four-year-old son to spend the day together. They had plans for the Bronx Zoo, just a father and son wandering among animals and sunshine, building memories to fill the space between visits.

Conor was staying with his mother in her high-rise apartment on East 57th Street in Manhattan—53 floors above the city. While they waited for Eric to arrive, the building’s maintenance crew was cleaning windows. One janitor had opened a large living room window to wash the exterior glass.

Conor was a bright, joyful child—curious, full of life. He ran through the apartment, laughing and calling for his mom, excited to see his dad. He didn’t know that the window, which had always been closed, was now open. He thought the glass was still there.

He ran toward it.

And in an instant that no one could stop, he fell.

Fifty-three stories.

By the time Eric Clapton arrived at the apartment, the sirens were already there. Police, paramedics, neighbors standing frozen in disbelief. His son was gone.

There are losses so immense that the mind simply refuses to process them. The death of a child isn’t just an ending—it’s the erasure of every possible future. Every birthday, every hug, every bedtime story, every “I love you, Dad.” All of it, gone in a moment that replays endlessly in a parent’s mind, a wound that never closes.

For Clapton, music had always been a refuge—a place where pain could become beauty, where words could turn into truth. But after Conor’s death, even that was gone. His guitars sat untouched. The silence in his home mirrored the silence in his heart. For weeks, he couldn’t play a note. To make music seemed obscene when his son no longer existed.

But grief has its own language. It demands to be spoken, even when the words tear you apart. Slowly, painfully, Clapton began to reach for his guitar—not because the pain had faded, but because music was the only vessel strong enough to hold it.

Out of that darkness came “Tears in Heaven.” Co-written with lyricist Will Jennings, it became one of the most haunting songs ever written about loss.

“Would you know my name if I saw you in heaven?

Would it be the same if I saw you in heaven?”

Every word is raw—an open wound turned into melody. It’s not just a song about death; it’s a plea from a father asking the only question left after tragedy: will my child still remember me when we meet again?

When the song was released in 1992 on Clapton’s Unplugged album, it shattered people in the best possible way. It won three Grammy Awards, but its true impact couldn’t be measured in trophies. “Tears in Heaven” became an anthem for anyone who had lost someone they couldn’t imagine living without. Parents who’d buried children. Spouses, siblings, friends—people who’d carried unbearable grief in silence suddenly had words that spoke for them. The song told them they weren’t alone.

For years, Clapton performed “Tears in Heaven” at nearly every show. Audiences would cry, some standing silently, others mouthing the lyrics with closed eyes. But for Clapton, each performance was its own form of torture. Every time he sang those lines, he relived the worst day of his life.

Eventually, in the 2000s, he stopped performing it. “I didn’t feel the loss anymore,” he said later. “And that loss was such a part of performing the song. It was time to let it rest.”

But Conor’s death had already transformed him. His sobriety, which had begun a few years earlier, became ironclad. Staying sober was no longer about health or fame—it was about honoring his son. About being the kind of man Conor could have looked up to.

In 1998, Clapton founded the Crossroads Centre in Antigua, a treatment facility for people battling addiction. He’s funded it through benefit concerts for decades, helping thousands reclaim their lives. It was his way of turning unbearable pain into purpose. The center became his promise to Conor—that his death would not be meaningless.

Today, Eric Clapton is 79 years old and has been sober for nearly four decades. He rarely speaks publicly about Conor, but when he does, there’s a stillness in his words—a quiet understanding that some pain never leaves. Parents who have lost children know this: the grief doesn’t disappear; it changes form. It becomes part of you, like a scar woven into your soul. You learn to live with it, not beyond it.

For Clapton, that grief is both burden and fuel. It lives in his music, in the foundation he built, in the life he continues to live with purpose and humility. Through his pain, he’s given millions of others permission to feel their own. “Tears in Heaven” isn’t just about Conor—it’s about every loss too heavy for words. It says: your love still matters, even in the face of unimaginable absence.

Conor Clapton lived only four short years, but his impact rippled far beyond what most lives ever achieve. He changed his father, and through that, changed music itself. The tragedy that took him also gave birth to one of the most powerful songs ever written—a song that continues to remind people around the world that love, even when cut short, never really dies.

The brightest lights often burn the shortest. But their warmth—like a song born from pain—can last forever.